AFD, GPE, IIEP Workshop. 2005 – 2025: Two Decades of Aid Effectiveness in Education

Policy Brief from IIEP, AFD and GPE: Renewing the Promise of Development Effectiveness for Transforming Education

Investment in education, in terms of both quantity and quality, must be put back at the heart of national and international priorities. Since 2005, the share of international aid allocated to education has dropped sharply, falling below 6% in 2023. At the same time, fragmentation is increasing: ministries of education deal with dozens of implementing agencies and manage a proliferation of micro-projects, resulting in unsustainable transaction costs. This analysis of the past two decades reveals four persistent systemic obstacles and provides four recommendations for effective cooperation in education.

NORRAG’s contribution to the IIEP, AFD and GPE evidence workshop

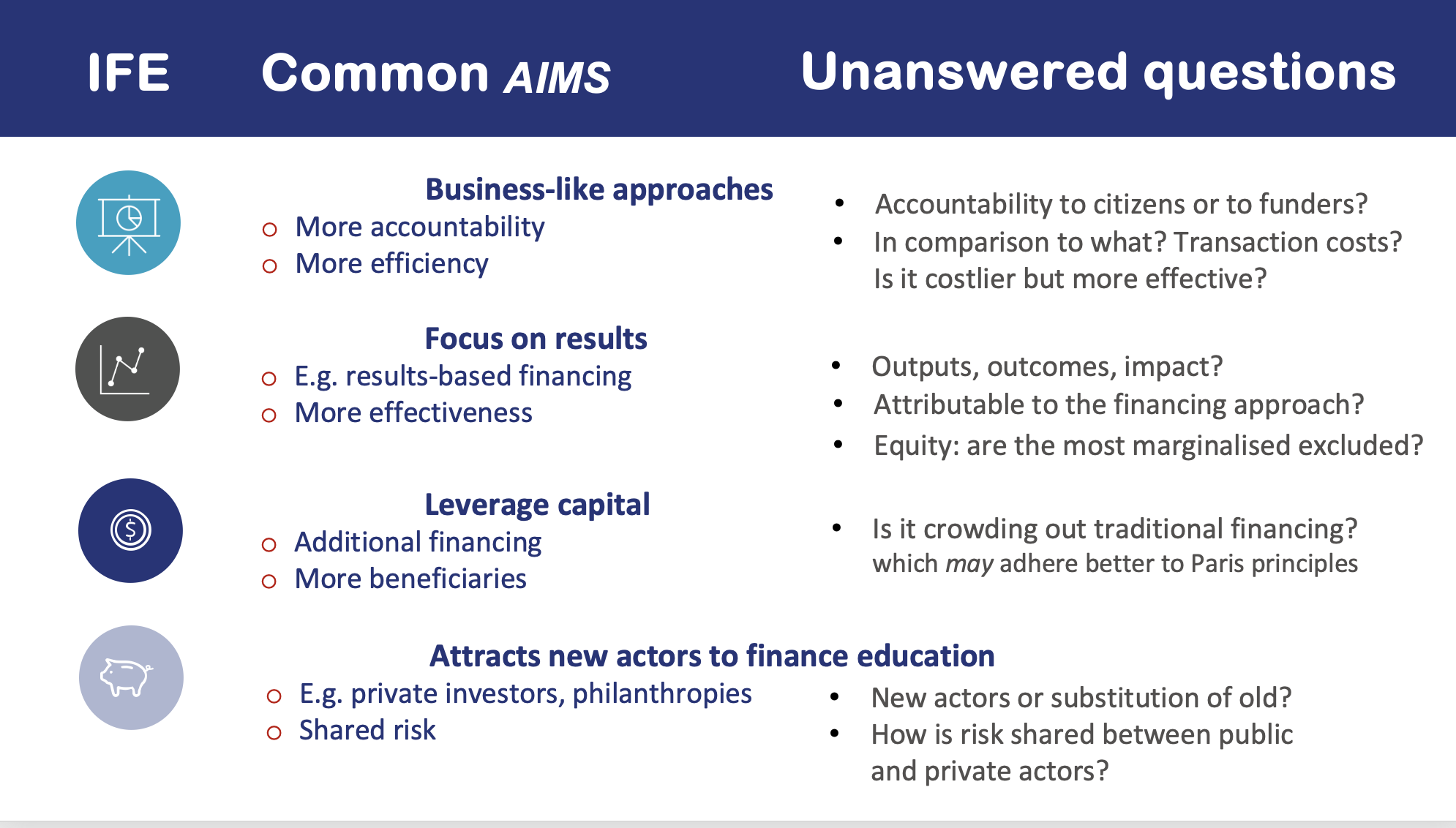

New frontiers in Education Financing and Perspectives

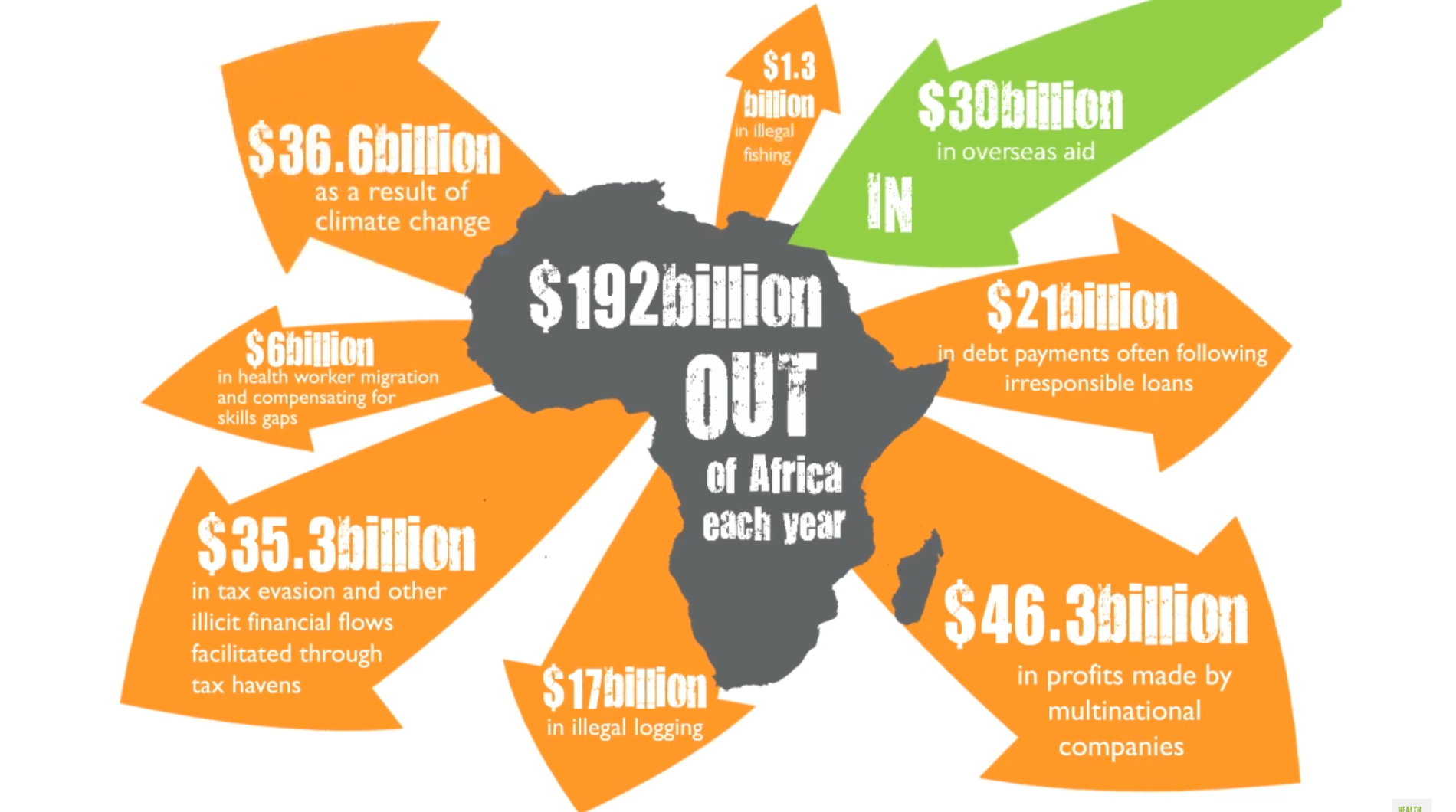

The debate on how to increase education financing is longstanding. Before 2005, emphasis was placed on taxation and domestic resource mobilisation, including strategies to broaden the tax base and strengthen government accountability. Post-2005, especially in the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) era, the focus shifted towards innovative financing, framed as a way to mobilise additional resources and achieve systemic educational gains. However, donor contributions to education have in many cases declined, with some donors justifying reductions on the assumption that private or innovative financing will fill the gap—an assumption not supported by current evidence.

Key Takeaways

- Evidence on innovative financing’s effectiveness remains limited.

- Promises of scale and systemic change are often overstated.

- Public financing continues to underpin most “private” mechanisms.

- Substitution risks are real: some donors reduce traditional aid while funding innovative mechanisms.

- Clear distinctions are needed between efficiency and effectiveness, outputs and outcomes.

The Promise of Innovative Finance

Innovative financing is rhetorically presented as offering “more and better” funding—more resources, better results, improved efficiency, stronger equity, and system transformation. Yet evidence of these benefits is limited. Promises often remain aspirational, and mechanisms may not consistently deliver the intended outcomes. Distinctions between “efficiency” (doing things more cheaply) and “effectiveness” (achieving desired outcomes) are often blurred.

Not Just the Private Sector

Despite common perceptions, innovative financing is not limited to private capital. In Latin America, for instance, government budgets have supported innovations such as conditional cash transfers. Even mechanisms marketed as “private sector” (e.g., development impact bonds) usually rely on public funding at some stage—design, outcomes funding, or guarantees. Rather than relying on private money, even private mechanisms rely on public money catalysing private capital at scale, or public money de-risking private investment.

What Does “Investment” Mean, and What Will Be Paid Back?

For governments, the “return” on education investment is social development and learning outcomes. For financial actors, investment implies monetary repayment—capital plus interest. This divergence creates tensions. Current assumptions—e.g., that economic growth will allow repayment of education loans—may not hold given global financial volatility. Thus, clarity is needed on what “payback” entails in education financing. In the same way as public debt is currently being reconsidered (through debt swaps or calls for a Jubilee debt forgiveness), we should also be critically analysing the debt that will accrue through private investments.

Conventional IFE and the Paris Declaration (2005) and Busan Partnership (2011)

The Paris Declaration (2005) and Busan Partnership (2011) set aid effectiveness principles: ownership, alignment, harmonisation, managing for results, mutual accountability, predictability, and use of partner systems. Overall, innovative financing mechanisms have not been systematically assessed against aid effectiveness benchmarks. Therefore systematic evidence linking innovative financing to these principles is limited. However, initial expert analysis indicates that:

- Ownership: mixed

- Alignment to national priorities: mixed; can follow funder preferences instead

- Harmonisation of donors: usually individual donor projects, or two or three collaborating (e.g. public derisking private investor)

- Results orientation exists, but results are often narrowly defined (e.g., enrolment rather than learning).

- Mutual accountability is largely absent, but accountability to funders is strong.

- Predictability is largely absent in short term private mechanisms.

- Use of partner systems is minimal, with most IFE requiring additional reporting systems.

Key Questions to Ask

When considering innovative financing for education, stakeholders should ask:

- Is the mechanism appropriate for the context?

- Will it genuinely bring additional finance, or substitute existing aid?

- What evidence supports its impact claims?

- What results are measured (outputs vs. learning outcomes)?

- Does it strengthen or bypass national systems?

- Who bears the risks, and who benefits from the returns?

- Is the approach ambitious enough to address systemic challenges (1) in education and (2) in development financing (in FFD4 agenda and TES Action Track 5)

Find more on NORRAG’s Special Issue 05