Citizen-Led Assessments in Pakistan: Between Promise, Practice, and Policy Influence

In this blogpost, Sehar Saeed reflects on the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), ahousehold-based initiative that aims to provide reliable data on the reading and arithmetic skills of children aged 5–16 through citizen-led assessments in Pakistan.

Why ASER? Origins and Government Engagement

ASER Pakistan (Annual Status of Education Report) was launched in 2008 by Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi (ITA), not as a government initiative, but as a civil society-led response to the absence of reliable, timely data on what children were learning—particularly outside the formal system. At the time, national assessments and provincial assessments were infrequent, school-based, and often excluded out-of-school children or those in non-state institutions.

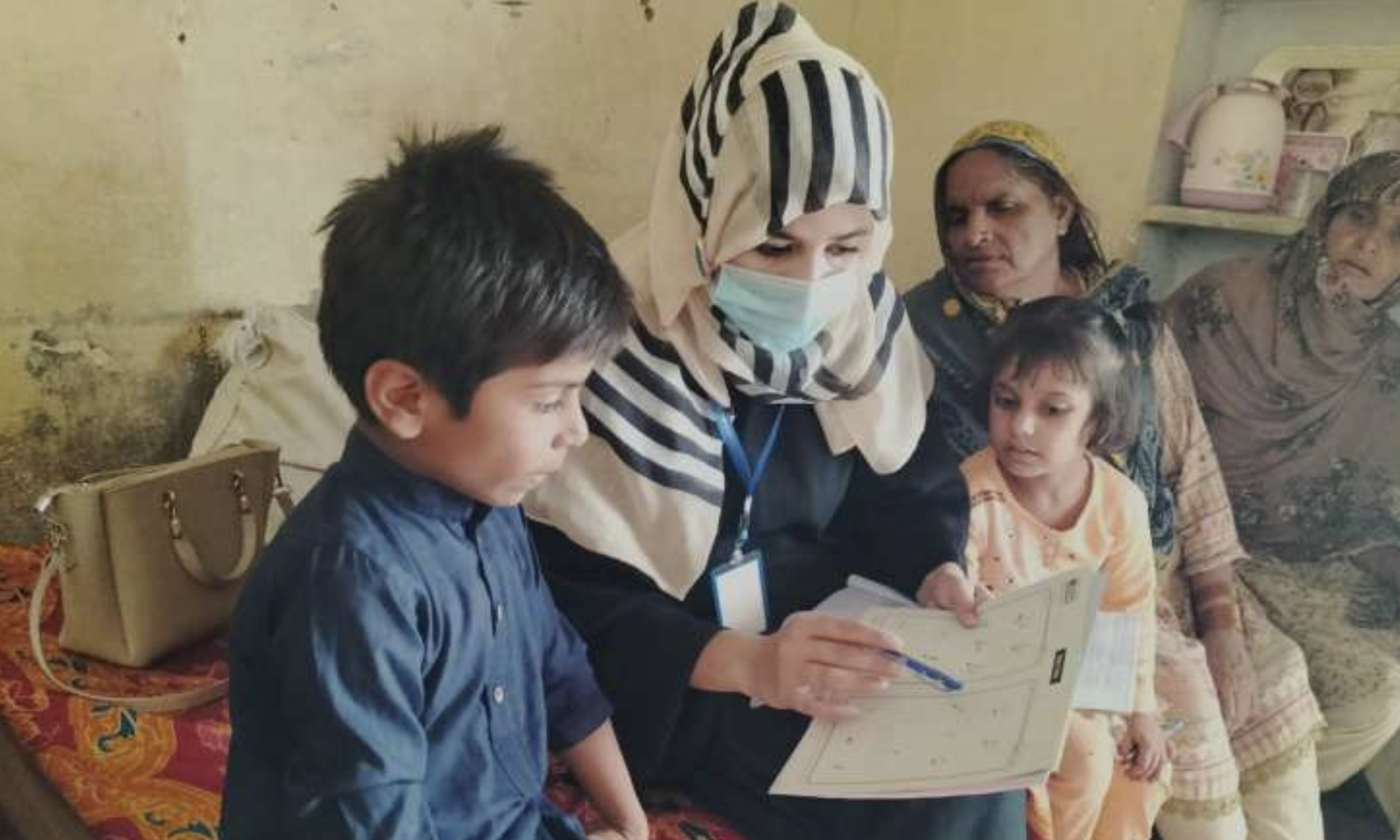

ASER’s approach is simple yet radical: train citizens—students, teachers, activists—to visit households and assess basic reading and arithmetic skills of children aged 5–16 using easy-to-administer tools adapted from early grade curricula. The household model meant that children both in and out of school were included, disrupting assumptions that enrollment alone was a sufficient indicator of progress.

What Is Being Tested—and What Happens to the Data?

ASER assessments focus on foundational literacy and numeracy: Can a child read a grade 2-level story? Solve a two-digit subtraction problem? The tools are oral, contextually translated, and designed to be non-threatening—administered in the child’s home, often by someone from their own community.

The collected data, disaggregated by gender, wealth, disability, school type, and mother’s education, allows for a granular view of learning inequalities. The data is publicly accessible and used for both national advocacy and sub-national dialogue. ASER findings have featured in:

- The Economic Survey of Pakistan and Global Education Monitoring Report.

- Provincial Sector Plans, such as Sindh’s 2019–2024 plan, which included ASER data to inform strategies for early grade improvement.

- The District Education Performance Index (DEPIx) 2024, which incorporated ASER indicators to shift focus from inputs to outcomes.

- Pakistan’s Foundational Learning Hub (2023–2025), which now references CLA data as a supplementary input for SDG monitoring.

However, the influence of ASER data often hinges on perception. While some provinces have integrated its findings into strategy and funding decisions, others view it as supplementary at best. The real challenge lies not in the credibility or consistency of the data itself, but in making it universally useful and valued—seen not as external or optional, but as a relevant benchmark for all stakeholders. Its uptake depends largely on the willingness of decision-makers to recognize community-generated evidence as legitimate, timely, and actionable. Until such perceptions shift, the potential of citizen-led assessments to drive systemic reform will remain unevenly realized.

From Margins to Mainstream: Citizen Data and the Copenhagen Framework

The legitimacy of citizen-led assessments received a major boost in March 2025, when the UN Statistical Commission formally adopted the Copenhagen Framework on Citizen Data. Developed by the UN Statistical Division over two years, the Framework establishes principles for integrating citizen-generated data into national and global monitoring systems—especially for tracking the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The Framework explicitly acknowledges the value of systematic, community-driven assessments in filling data gaps, particularly on marginalized populations and education equity. It urges national statistics offices (NSOs) and governments to collaborate with citizen data producers and include them in deliberative processes.

For ASER Pakistan, this recognition is more than symbolic. It affirms years of grassroots work as part of a legitimate and necessary data ecosystem. Already, bodies like the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics and the Pakistan Institute of Education (PIE) are working in close coordination with the ASER Pakistan team to align citizen-generated insights with national monitoring systems. As part of this collaboration, ASER Pakistan will work with PIE and PBS to produce a nationally representative sample for the 2025 survey, ensuring that citizen-led assessments are both methodologically rigorous and officially recognized across the country.

Global Tools, Local Realities: Balancing Alignment, Relevance, and Accountability

ASER Pakistan is a founding member of the People’s Action for Learning (PAL) Network, a South-South coalition coordinating citizen-led assessments across over 15 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In response to long-standing critiques—such as the use of a single tool for children aged 5 to 16, which limits age-appropriateness, and the lack of cross-country comparability due to homegrown tools—the PAL Network has developed a second generation of assessment tools. These include the International Common Assessment of Numeracy (ICAN), ELANA (Early Language and Literacy and Numeracy Assessment), and now ICAN-ICARe, all aligned with SDG 4.1.1a and the Global Proficiency Framework (GPF), enabling harmonized reporting of foundational learning across diverse contexts.

ASER Pakistan has actively contributed to piloting and refining these tools in local settings. For example, ICAN in Pakistan was translated into regional languages as well as Braille and Pakistan Sign Language, and implemented by trained volunteers to ensure accessibility and cultural relevance. These adaptations demonstrate that alignment with global frameworks need not compromise local relevance; rather, they can be reshaped through inclusive, participatory processes that remain rooted in communities.

Still, citizen-led assessments like ASER must contend with persistent structural and operational challenges. Sustainability remains a key concern, as the model relies heavily on a vast but transient volunteer base. While this enables wide reach, it raises questions about consistency and long-term scalability. Sampling frameworks have also posed limitations—ASER historically employed different approaches for rural and urban areas, making it difficult to present a fully unified, nationally representative picture of learning outcomes. Political receptivity is uneven—while some provinces embrace ASER data for policy and planning, others dismiss or sideline it, especially when it disrupts official narratives.

Such critiques are not only valid but essential—they compel CLA actors to engage in deeper reflection, strengthen their practices, and ensure that evidence leads to meaningful and lasting change. ASER Pakistan, in this spirit, continues to evolve—responding to feedback through innovations such as the move toward a nationally representative sample in 2025 and ongoing efforts to enhance credibility, utility, and impact.

Conclusion: Making Data Work for Justice

Citizen-led assessments like ASER are not silver bullets. They cannot substitute for strong public systems. But what they offer is vital: data that is participatory, disaggregated, and grounded in lived reality. In a world of widening learning inequalities and climate-driven disruptions, such tools offer both diagnosis and dialogue.

An ASER reading card, whether in the hands of a mother in Tharparkar or a policymaker in Islamabad, is not just a test—it is an invitation. To ask harder questions. To demand better systems. To see all children, not just those who make it to school. When citizens are trusted to count, they do more than measure—they advocate, challenge, and lead.

Acknowledgements

We thank the over 150,000 volunteers, 50 partner organizations, NCHD, the Pakistan Institute of Education (PIE), the Pakistan Foundational Learning Hub, the Ministry of Federal Education and Professional Training, Provincial and Area Departments of Education, MoPD&SI, and the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics for shaping this journey. ASER Pakistan by ITA @25 continues to be a story of learning for all—by the people, for the people.

Author

Sahar Saeed is a seasoned education specialist with over 12 years of experience in research, program design, and policy engagement in Pakistan’s education sector. As Deputy Director of Research at ITA and a PAL Research Fellow, she leads large-scale studies on foundational learning and contributes to cross-country evidence on learning equity and systems reform.