Ethiopia’s Education Crisis Continues – Millions are Left with Uncertainty

In this blogpost, Tebeje Molla outlines the scale, root causes, and implications of the deepening crisis of Ethiopia’s education system.

The Deepening Crisis of Ethiopia’s Education System

Ethiopia’s education system has been marked by a long-standing and deepening crisis that predates, yet has been significantly exacerbated by, recent conflicts and the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite sustained expansion in access to schooling over the past decades, gains in enrolment have not translated into commensurate improvements in quality, relevance, and equity.

This systemic fragility is most visible in three interconnected manifestations. First, persistently low pass rates in national examinations point to a profound learning crisis. Second, entrenched structural inequalities—linked to geography, poverty, and historical marginalisation—continue to shape unequal educational opportunities and outcomes. Third, in Amhara and other regional states, the destructive impacts of war have compounded these challenges by disrupting schooling, displacing learners and teachers, and undermining already fragile institutions.

A Persistent Pattern of Low Pass Rates

Ethiopia’s education system has faced deep-rooted challenges, with its secondary schools teetering on the edge of collapse. On 14 September 2025, Minister of Education Berhanu Nega announced that 536,962 students—over 91% of all examinees—failed to achieve the passing mark of 50% in this year’s Grade 12 examination, underscoring the severity of the crisis. Only 2,384 students scored 500 out of 600, highlighting the extreme rarity of top performance.

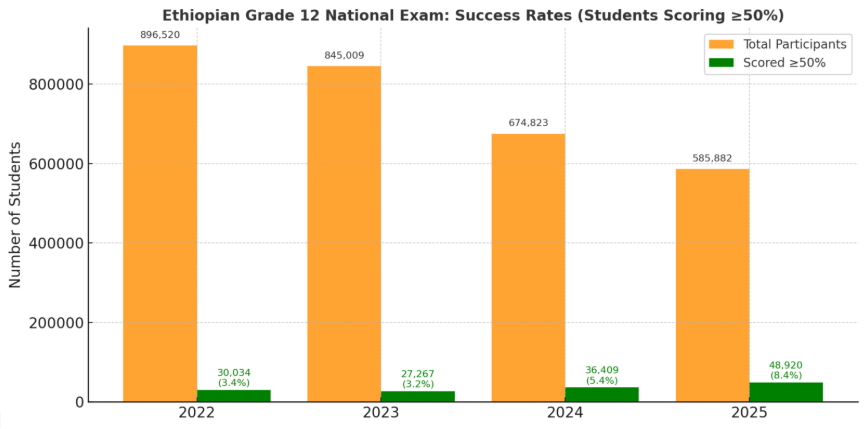

Over the past four years, more than three million students have sat for the national Grade 12 exam, yet over 95% failed to reach the 50% passing mark (see the graph below). In this year’s Grade 12 exam alone, out of almost 600,000 candidates, only about 49,000 passed (that is more than 91% of students failed to reach the 50% pass mark).

Source: Author based on publicly available exam result report

The crisis is systemic. It is not just a matter of a few schools underperforming or certain districts struggling. This year, over 1,200 secondary schools didn’t have a single student pass the national exam. Similarly, last year, over 1,300 schools recorded zero passes. While there are signs of improvement in recent years, the overall rate remains minimal. The four-year trend reflects a system in crisis: despite a slight upward shift, fewer than one in twenty students has been able to score 50 per cent or above.

Persisting Structural Inequality

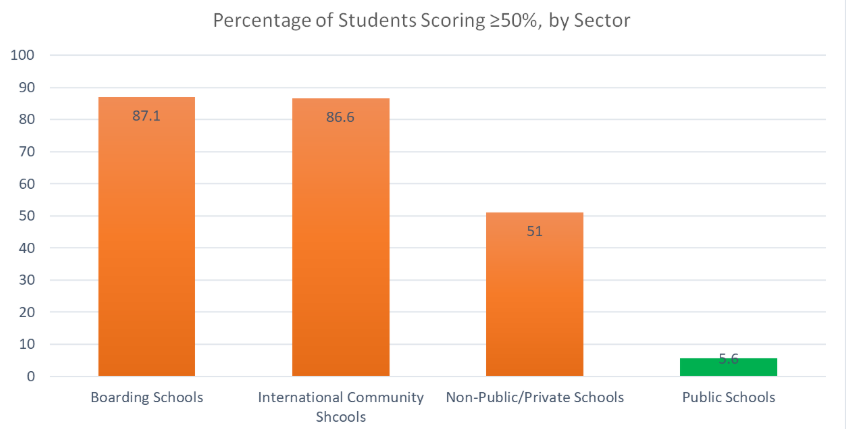

The stark disparities in exam results across Ethiopia’s schooling sectors highlight deep socio-economic inequalities. For instance, this year, 87.1% of students in government-funded boarding schools achieved a passing mark of 50% or above, closely followed by 86.6% of students in international community schools. Private schools ranked third, with just 51.6% of their students passing. Public schools, which educate the vast majority of rural communities and the urban poor, fared far worse, with only 5.6% of students reaching the passing mark.

Source: Author based on publicly available exam result report

The gender disparity is also stark. Of the 48,929 students who passed, only 18,478 were female, representing just 38% of the successful cohort. Similarly, of the 2,384 high achieving students that scored above 500 out of 600, only 742 (31%) were female.

The Cost of War

Hundreds of schools have been closed due to war and instability in the major regional states of Amhara, Tigray, and Oromia. The impact is evident in the drop of total number of Grade 12 students who sat for the national exam (see the graph) from almost 900,000 in 2022 to fewer than 600,000 in 2025. Conflict has disrupted schooling, displaced families, and prevented hundreds of thousands of young people from sitting the exam at all.

According to the Ethiopia Education Cluster, a coordination body led by the Federal Ministry of Education in partnership with UNICEF and Save the Children, over 9 million children are out of school.

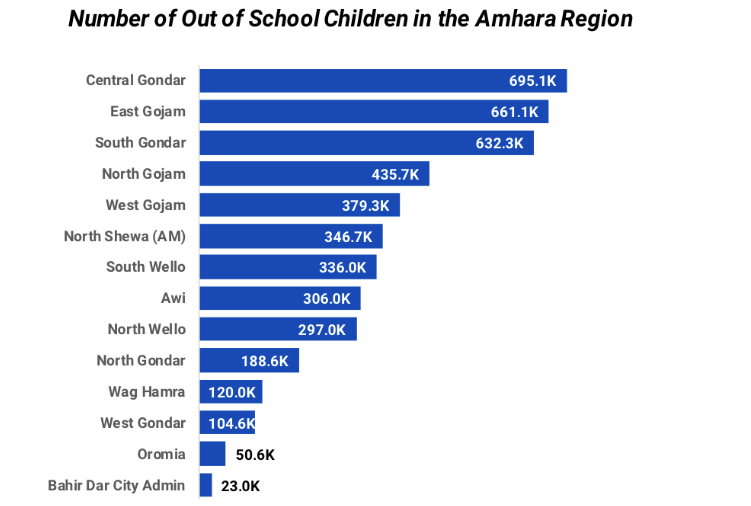

Within the Amhara Region, as data from EEC (see the graph below) show, in the Central Gonder zone alone, close to 700,000 children are out of school. The same source indicates that in North Gojam, over 90% of school-aged children have no access to formal education.

Source: EEC (2024)

In 2024, the Amhara Regional Government aimed to enrol over 7 million students for the following academic year. However, widespread conflict meant that only 2.3 million students were actually enrolled. Armed conflict, political instability, and repeated disruptions over the past two years have left more than 4.4 million children out of school.

Last week, the Amhara National Regional Government reported that, in the current (2025/26) academic year, more than three million children—approximately 42% of the school-aged population in the Region—are out of school due to the ongoing conflict. The situation is particularly severe in secondary schools, where 64% of students have no access to education. In addition, over 23,000 teachers from closed or damaged schools have not returned to work.

Consequences of the Education Crisis

At the personal level, the consequences of Ethiopia’s education crisis are severe and enduring. For many young people, failing the Grade 12 examination closes the door to university education and formal employment opportunities, locking them into cycles of unemployment and long-term disadvantage. Confronted with a lack of prospects, some are driven by desperation to embark on perilous journeys across deserts and borders in search of a better future, often at great personal risk. The loss of these opportunities not only limits individual life chances but also erodes hope and motivation among young people.

At the societal level, the exclusion of an entire generation from educational success threatens Ethiopia’s social and economic future. The systematic underdevelopment of human capital undermines national capacity for innovation, productivity, and democratic participation. With millions of young people unable to contribute their skills and knowledge, the country risks deepening inequality, entrenching instability, and forfeiting the long-term benefits that a well-educated population can bring. The crisis, therefore, represents not only an individual tragedy but also a profound collective loss.

What Can Be Done?

Reflecting on the latest national Grade 12 exam results, one social media commentator expressed deep frustration: “The message of this result is that in this country schooling is just a waste of time.” The sense of disillusionment with the education system is widespread. It deserves public attention.

The first step in turning a crisis into change is the will to confront reality. In this regard, despite the seriousness of the crisis, the government appears more focused on its symptoms than its root causes. The Minister of Education has attributed the low pass rate to tighter controls on cheating. Yet cheating is itself a symptom of deeper problems rather than the cause. Further, on 15 September, Ayelech Eshete, State Minister for General Education in Ethiopia, emphasised the role of parents in shaping academic outcomes. While parental support is important, context matters. Many students come from rural farming communities and low-income urban households, where parents face daily struggles to make ends meet. Expecting these families to provide the same level of educational support as more advantaged households overlooks the very real challenges they face.

It is time that the nation faces the structural issues behind the crisis with honesty and clarity. Addressing Ethiopia’s education emergency requires coordinated, multifaceted action, including:

Ending the violence. The brutal conflict in Tigray, compounded by armed resistance in Amhara and Oromia, has destabilised the country. Armed groups such as Fano and the Oromo Liberation Front have weakened government control and disrupted education in affected regions. Peaceful resolution of conflicts and a secure environment for schools must be central to national policy to protect students’ right to learn.

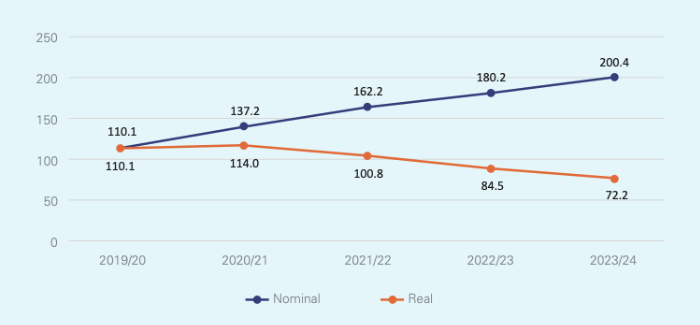

Investing in education. Education appears to be a low priority for the current government. World Bank data show that Ethiopia’s expenditure on education as a share of GDP fell from 5.5% in 2017 to 3.7% in 2022. The latest UNICEF budget brief shows that, in Ethiopia, Real educational spending has declined from 110 billion birr in 2019/20 to 72 billion birr in 2023/2024. The following graph show the nominal and real education spending (in billion Ethiopian Birr).

Source: UNICEF (2024)

At present, government priorities appear tilted towards high-visibility infrastructure projects, such as parks and paved roads in the capital. Without a skilled, educated workforce to sustain these developments, such “flashy” projects risk remaining superficial. Human development is the foundation of sustainable progress. The government must prioritise education funding.

Improving teacher quality and morale. Teachers in Ethiopia are often drawn from underachieving students, and the quality of initial teacher education and professional learning opportunities has long been insufficient. Teaching is also poorly paid, undermining morale and performance. Immediate investment in teacher training, professional development, and fair remuneration is essential to raise educational standards nationwide.

Closing the gap in educational access. As the second graph above shows, exam results show that students from rural areas, small towns, and disadvantaged urban communities consistently score at the bottom, highlighting stark inequalities. Targeted interventions—such as additional resources, infrastructure, and support programs—are urgently needed to ensure all children have equitable access to quality education.

Ethiopia’s education crisis demands honest, inclusive, and forward-looking dialogue that tackles root causes rather than symptoms—only then can decisive action transform challenges into lasting opportunities for students and the nation.

The Author:

Tebeje Molla, Associate Professor and ARC Future Fellow, School of Education, Deakin University, Australia