Introducing “Developmentally Aligned Design”: When Child Development Becomes an Ethical Compass for AI

In this blog post, which is part of NORRAG’s blog series on “AI and the digitalisation of education: challenges and opportunities”, Nomisha Kurian advocates for Developmentally Aligned Design (DAD) of AI that is adapted to the child’s level of development and ensures that AI respects the child’s sensory and emotional boundaries.

In the crowded world of AI ethics, philosophy, law, and sociology have long dominated the conversation. These disciplines are invaluable – however, they often circle around adult experiences, abstract principles, and high-level governance. What if we treated the science of child development – long familiar to educators – as an ethical lens in its own right? What if the benchmarks of what children can see, hear, remember, and understand became well-recognised design foundations for AI systems in education and children’s lives more broadly?

My new paper in AI, Brain and Child introduces the framework of “Developmentally Aligned Design” where I anchor ethical AI design in the lived realities of early human growth. In AI ethics circles, “alignment” is a term frequently used to mean making sure technology follows human values. But what if we talked about another kind of alignment – developmental alignment, shaped around the ways children see, think, and grow?

For decades, early childhood education has embraced “developmentally appropriate practice” (DAP): the commitment to match how we teach and care for children to their unfolding capacities and vulnerabilities. Developmentally Aligned Design (DAD) proposes an algorithmic successor to that tradition – a way to hard-code the rhythms of childhood into AI’s data, interfaces, and behaviours.

Why This Matters as AI Rushes Into Classrooms

In nurseries, living rooms, and primary schools, AI tools are already telling stories, correcting reading errors, and fielding children’s questions. But most have been tuned to adult defaults – expecting attentional stamina, reasoning skills, and emotional regulation that children are still acquiring. This can result in children engaging with tools not optimally designed for their developmental needs – AI interfaces that overwhelm the senses, dialogue that blurs the line between human and machine, and learning sequences that leave children frustrated rather than encouraged.

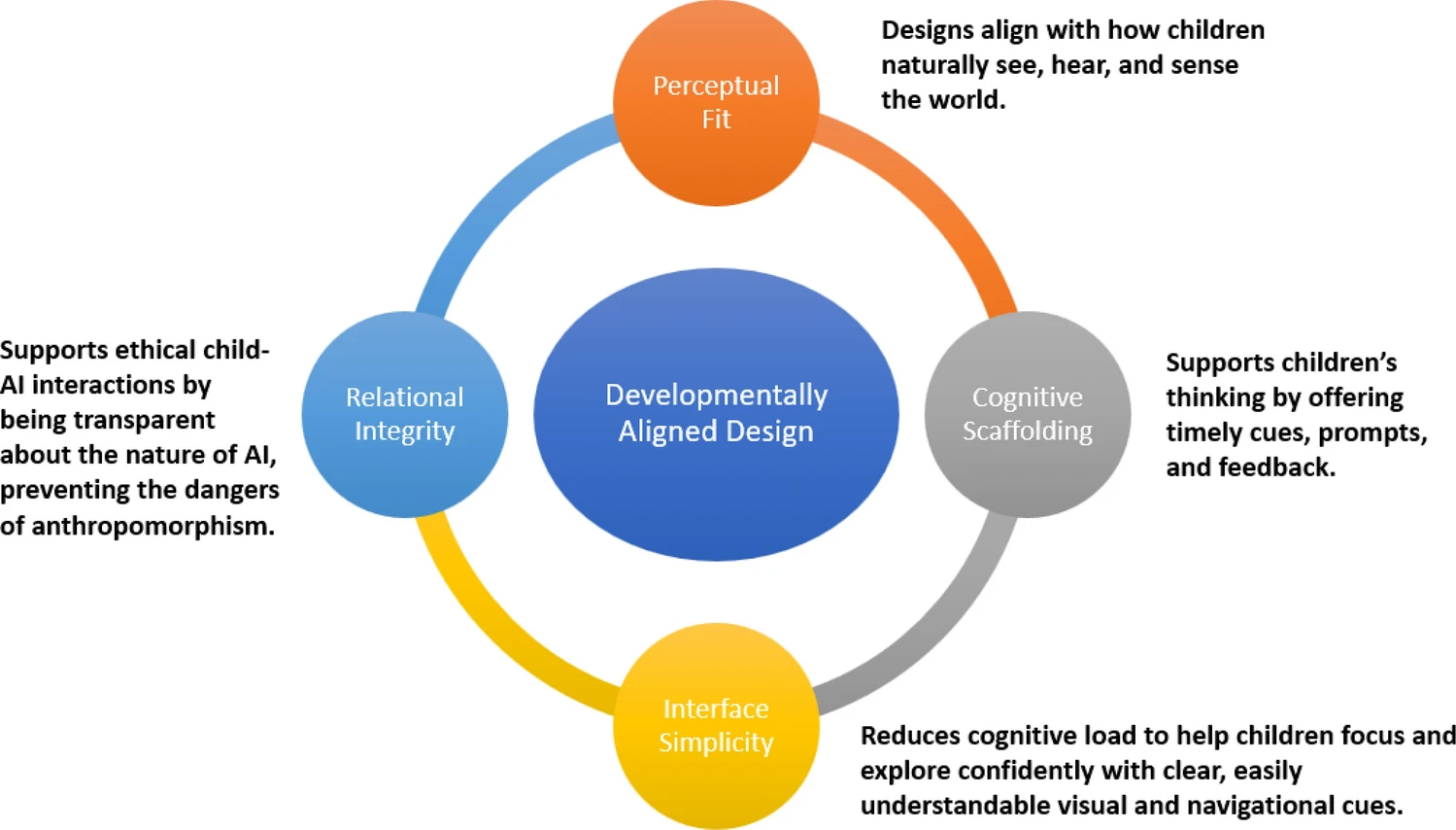

The DAD framework responds to these risks by making developmental science a core design input. Its four pillars – Perceptual Fit, Cognitive Scaffolding, Interface Simplicity, and Relational Integrity – explore what it means to respect the rights, dignity, and agency of children in AI design.

Fig. 1: A visual summary of the framework, retrieved from the paper here.

Relational Integrity: Guarding the Boundaries of Trust

Of all DAD’s pillars, Relational Integrity most explicitly tackles the ethics of influence. Children – particularly young children – are prone to anthropomorphise responsive technology, attributing feelings, intentions, and social obligations to it. Without clear boundaries, AI can unintentionally over-rely on these bonds to drive engagement, capture data, or shape behaviour.

Relational Integrity sets strict guardrails: self-identification in child-friendly language (“I’m a computer helper, not a person”), bans on manipulative emotional prompts (“I’m sad when you leave”), visual cues to signal the mechanical nature of an AI’s thinking (and clearly differentiate it from a human brain), and session ceilings to prevent over-attachment. It also includes safety protocols for handling personal disclosures, ensuring that AI does not become a confidant in place of a safe adult.

In ethical terms, this is about respect for children who are still working out the boundaries of identity, and a commitment to supporting their developing understanding of self and others.

Perceptual Fit: Respecting Sensory Boundaries

Perceptual Fit focuses on how the concrete details of AI design (e.g. visuals, sound, interaction pace) must match a child’s sensory capacity. Rooted in non-maleficence – do no harm – this principle guards against cognitive overload, stress, and diminished attention caused by fast, cluttered stimuli. Unlike adults, children’s senses are still maturing; they may not distinguish sounds well or manage fine motor tasks. As the paper explores, research links rapid digital media to later attentional deficits and weaker working memory, making slow-paced, uncluttered design an ethical necessity. For instance, a reading app should both recognise the natural stumbles of toddler speech (“wabbit” for “rabbit”) and include sensory pauses to protect attention. Perceptual Fit is thus a commitment to safe, gentle design – ethics translated into pixels and frames per second.

Cognitive Scaffolding: Keeping Learning in the Zone

Cognitive Scaffolding keeps tasks in Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development – just beyond what a child can do alone, but achievable with support. AI should build confidence by adapting difficulty to demonstrated mastery, fading hints, and offering metacognitive prompts, rather than pushing too far and causing stress or demotivation. For example, a math AI might break problems into smaller steps or raise difficulty only after mastery. DAD does not treat scaffolding as just a pedagogical choice, but also frames it as an ethical responsibility: adaptive AI must nurture self-efficacy and equity, acting as a supportive guide, not a harsh taskmaster.

Interface Simplicity: Preserving Mental Bandwidth

Interface Simplicity is a commitment to respecting children’s cognitive capacities. Complex menus, dense icon arrays, and inconsistent navigation do not just frustrate young users; they systematically disadvantage those with less developed working memory and selective attention.

By capping menu depth, limiting on-screen options, and keeping a persistent “home” anchor, DAD ensures that a child has as fair a chance as possible to use a tool effectively. This levelling of the playing field is an ethical stance against designs that privilege older, more cognitively mature users in spaces marketed for children.

In a digital education market that often rewards “feature-rich” products, Interface Simplicity is a distinctive move: a reminder that enough can be better than more when the user is still learning to filter and focus.

From Principle to Practice

The paper maps out how DAD principles can be carried through the entire AI lifecycle (dataset → model → UX → audit). Perceptual Fit influences dataset curation (e.g., including toddler speech in training corpora), Cognitive Scaffolding shapes model objectives, Interface Simplicity guides UX design, and Relational Integrity is embedded from design to post-deployment – from filtering manipulative language in training data to auditing child-AI interactions after release.

This end-to-end approach reframes child development expertise as a strategic asset in AI engineering (and moves beyond a post-hoc compliance check). It invites educators, developmental psychologists, and child-rights advocates into the earliest design conversations, alongside data scientists and product managers.

Why This Ethical Lens Is Urgent

As AI accelerates the digitalisation of education, the stakes for young children are high. Without developmentally aligned guardrails, AI risks:

- Overwhelming sensory systems and shortening attention spans

- Frustrating or demoralising learners by mis-scaling difficulty

- Creating inequities in digital access and comprehension

- Blurring relational boundaries in ways that invite manipulation or unsafe disclosure

These risks are measurable, foreseeable, and within reach to address. That makes their prevention a matter of ethics as much as engineering.

An Invitation to Co-Design the Future

Treating child development science as an ethical commitment means designing AI that moves at the child’s tempo, speaks in the child’s conceptual language, and respects the child’s sensory and emotional boundaries.

In that sense, DAD is both a design framework and a moral position: the belief that to serve children well, technology must first understand what it means to be a child.

If philosophy and sociology have given AI ethics its conscience, perhaps developmental science can give it its heartbeat.

The Author

Nomisha Kurian is Assistant Professor in the Department of Education Studies, University of Warwick. She focuses on responsible AI design for children and youth.