School Clustering Policy in Pakistan

In this blogpost by Sajid Ali, Aisha Naz Ansari, and Khadija Gul share the findings of an analysis of a 2021 school clustering policy in the Sindh province of Pakistan. The authors address the strengths and challenges of the policy and find that school clustering has the potential to bring about positive change if done well.

Over the years, multiple initiatives have been undertaken to enhance the quality of education in Pakistan. One such initiative was the clustering of schools, which aimed to provide education and facilitate the transition process in remote and scattered areas with meagre resources (Arain, 2023). This approach involved grouping several schools into a cluster managed by a well-resourced school within the cluster – Cluster Hub (School Education policy, 2016). The concept of school clustering originated in Latin America around 1940s and spread to numerous other countries as the nations of the developing world embraced it as a creative solution to financial constraints while addressing the growing demand for education without compromising on quality.

The School Clustering policy in the Sindh province of Pakistan was initiated in 2016, with an aim to create a delegated governance structure to improve education. Over time, some shortcomings were identified, including restrictive geographical coverage criteria not aligning with the local administrative setup, the lack of adequate cluster-based support mechanisms and ongoing training, an unclear trajectory for students, and limited availability of higher-grade schools. Consequently, in 2021, the policy was revised to address these issues and create a more effective school cluster system. The revised policy was drafted by the provincial School Education and Literacy Department to enhance decentralised education service delivery through school clustering. The primary objectives of the revised policy are to increase access and quality by clustering demographically isolated schools through improved governance.

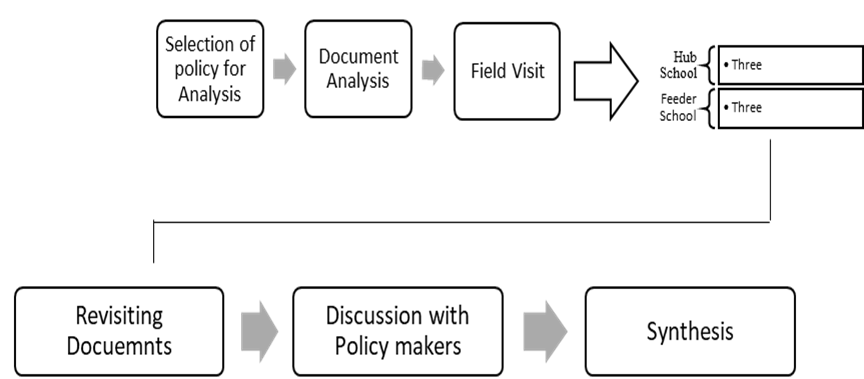

This blog shares the analysis of the 2021 School clustering policy against its intended objectives. To collect data for the analysis, six schools were selected from the three clusters including three hub cells and three feeder schools, as depicted in Figure 1. The analysis process also involved visiting the Reform Support Unit (RSU) and conducting six school visits to three clusters, mainly situated in slum areas: Cluster A, Cluster B, and Cluster C. Interviews were conducted with key stakeholders from RSU and UNICEF, as well as with head teachers from six schools, randomly selected guide teachers, subject teachers, and students. For the policy analysis, an adapted version of Rizvi and Lingard’s policy analysis framework was used.

Figure 1: Process of Policy Analysis

The policy analysis goes beyond examining the implementation and outcomes of the policy; it also involves a critical examination of the policy text, including the analysis and documentation of the discourses surrounding it (Taylor, 2004). Through this analysis, significant strengths, and weaknesses of the policy for increasing access and improving quality were revealed (Ali & Ansari, 2023).

The strengths of the policy included: availability of peer assistance, the provision of training manuals for continuous professional development (CPD) and the utilisation of drawing and disbursing officer (DDO) powers at cluster level. Additionally, the policy embraces support by Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) initiatives to supplement resources provided by the public sector. Some cluster schools were supported by private and non-governmental organisations through human and material resources.

However, the policy still faces persistent challenges. These include delays in the provision of essential resources, the unavailability of teachers due to the lack of timely replacements for retired or transferred staff, and the diversion of teachers to non-academic duties such as census activities. Additionally, the absence of translated CPD manuals, outdated monitoring and evaluation dashboards, and limited community engagement and parental involvement hinder effective implementation. Similar concerns around role ambiguity have also been highlighted by Arain and Fakir (2023). Moreover, broader socio-economic issues such as financial constraints, child labour, and early marriages continue to affect the quality of education by contributing to lower attendance rates and increased student dropouts. In response to such concerns, Ali (2006), in a study on cluster school policy in the Maldives, proposed a framework of providing sufficient resources and clear conceptualisation to enhance the effectiveness of the clustering policy.

The analysis indicates that the clustering policy is not merely symbolic in its implementation; rather, it has the potential to bring about a transformation in the education sector and in making the education accessible and of high quality, if implemented well. It is recommended that a greater involvement of community could enhance the effectiveness of school clustering policy. Further, a long-term continuous and field-based capacity building initiative should be employed for staff improvement. Last but not the least, it is important that the cluster staff and teachers are not transferred from a cluster at least for one academic year and particularly not during the academic session to sustain training and resulting improvements.

The Authors:

Khadija Gul is a Senior Research Assistant at the Aga Khan University Institute for Educational Development (AKU-IED). Her research primarily focuses on education policy, with a particular emphasis on the implementation of the school Clustering Policy. Her other areas of interest include educational policy, mental health, and English language and literature teaching. She has written on these issues in blogs and newspaper columns. kadija.gul@scholar.aku.edu

Aisha Naz Ansari is a research specialist at Aga Khan University Institute for Educational Development, Pakistan. She has published more than 25 research articles and research blogs in international and national journals and forums. Her research areas include systematic reviews, educational technology, educational psychology, teacher education, public-private partnerships, and classroom teaching and learning. aisha.naz22@alumni.aku.edu

Sajid Ali is Amir Sultan Chinoy Professor and Director of Research at Aga Khan University, Institute for Educational Development, Pakistan. He holds a PhD in Education Policy Studies from the University of Edinburgh, an MEd in Leadership and Policy from Monash University, and a Master’s in Sociology from the University of Karachi. He is the general secretary of the Pakistan Association for Research in Education (PARE). His research interests include globalisation and education policy, educational governance, education reforms, privatisation and public private partnerships in education. Dr Ali has contributed to the formation of various government policies, including the National Education Policy (2009); Teacher Licensing Policy; Sindh Education Sector Plan; Public Private Partnership Act and Non-Formal Education Policy of Sindh (2018).